Lucas Cranach the Elder Painting Reproductions 1 of 11

1472-1553

German Northern Renaissance Painter

Lucas Cranach the Elder (1472 – October 16, 1553) was a German painter.

He was born at Kronach in upper Franconia, and learned the art of drawing from his father. It has not been possible to trace his descent or the name of his parents. We are not informed as to the school in which he was taught, and it is a mere guess that he took lessons from the south German masters to whom Matthias Grunewald owed his education. But Grunewald practised at Bamberg and Aschaffenburg, and Bamberg is the capital of the diocese in which Cronach lies.

According to Gunderam, the tutor of Cranach's children, Cranach signalized his talents as a painter before the close of the 15th century. He then drew upon himself the attention of the elector of Saxony, who attached him to his person in 1504. The records of Wittenberg confirm Gunderam's statement to this extent that Cranach's name appears for the first time in the public accounts on the 24th of June 1504, when he drew 50 gulden for the salary of half a year, as pictor ducalis.

The only clue to Cranach's settlement previous to his Wittenberg appointment is afforded by the knowledge that he owned a house at Gotha, and that Barbara Brengbier, his wife, was the daughter of a burgher of that city.

The first evidence of his skill as an artist comes in a picture dated 1504. We find him active in several branches of his profession, sometimes a mere house-painter, more frequently producing portraits and altar-pieces, a designer on wood, an engraver of copper-plates, and draughtsman for the dies of the electoral mint. Early in the days of his official employment he startled his master's courtiers by the realism with which he painted still life, game and antlers on the walls of the country palaces at Coburg and Locha; his pictures of deer and wild boar were considered striking, and the duke fostered his passion for this form of art by taking him out to the hunting field, where he sketched "his grace" running the stag, or Duke John sticking a boar.

Before 1508 he had painted several altar-pieces for the Schlosskirche at Wittenberg in competition with Dürer, Hans Burgkmair and others; the duke and his brother John were portrayed in various attitudes and a number of the best woodcuts and copper-plates were published.

Great honour accrued to Cranach when he went in 1509 to the Netherlands, and took sittings from the Emperor Maximilian and the boy who afterwards became Charles V. Until 1508 Cranach signed his works with the initials of his name. In that year the elector gave him the winged snake as a motto, and this motto, or Kleinod, as it was called, superseded the initials on all his pictures after that date.

Somewhat later the duke conferred on him the monopoly of the sale of medicines at Wittenberg, and a printer's patent with exclusive privileges as to copyright in Bibles. The presses of Cranach were used by Martin Luther. His chemist's shop was open for centuries, and only perished by fire in 1871.

Relations of friendship united the painter with the Protestant Reformers at a very early period; yet it is difficult to fix the time of his first acquaintance with Luther. The oldest notice of Cranach in the Reformer's correspondence dates from 1520. In a letter written from Worms in 1521, Luther calls him his gossip, warmly alluding to his "Gevatterin," the artist's wife. His first engraved portrait by Cranach represents an Augustinian friar, and is dated 1520. Five years later the friar dropped the cowl, and Cranach was present as "one of the council" at the betrothal festival of Luther and Katarina von Bora.

The death at short intervals of the electors Frederick and John (1525 and 1532) brought no change in the prosperous situation of the painter; he remained a favourite with John Frederick I, under whose administration he twice (1531 and 1540) filled the office of burgomaster of Wittenberg. But 1547 witnessed a remarkable change in these relations. John Frederick was taken prisoner at the Battle of Mühlberg, and Wittenberg was subjected to the stress of siege. As Cranach wrote from his house at the corner of the marketplace to the grand-master Albert of Brandenburg at Königsberg to tell him of John Frederick's capture, he showed his attachment by saying, "I cannot conceal from your Grace that we have been robbed of our dear prince, who from his youth upwards has been a true prince to us, but God will help him out of prison, for the Kaiser is bold enough to revive the Papacy, which God will certainly not allow." During the siege Charles bethought him of Cranach, whom he remembered from his childhood and summoned him to his camp at Pistritz. Cranach came, reminded his majesty of his early sittings as a boy, and begged on his knees for kind treatment to the elector.

Three years afterwards, when all the dignitaries of the Empire met at Augsburg to receive commands from the emperor, and Titian came at Charles's bidding to paint Philip of Spain, John Frederick asked Cranach to visit the Swabian capital; and here for a few months he was numbered amongst the household of the captive elector, whom he afterwards accompanied home in 1552.

He died on the 16th of October 1553 at Weimar, where the house in which he lived still stands in the marketplace.

The oldest extant picture of Cranach, the "Rest of the Virgin during the Flight into Egypt," marked with the initials L.C., and the date of 1504, is by far the most graceful creation of his pencil. The scene is laid on the margin of a forest of pines, and discloses the habits of a painter familiar with the mountain scenery of Thuringia. There is more of gloom in landscapes of a later time.

Cranach's art in its prime was doubtless influenced by causes which but slightly affected the art of the Italians, but weighed with potent consequence on that of the Netherlands and Germany. The business of booksellers who sold woodcuts and engravings at fairs and markets in Germany naturally satisfied a craving which arose out of the paucity of wall paintings in churches and secular edifices. Drawing for woodcuts and engraving of copperplates became the occupation of artists of note, and the talents devoted in Italy to productions of the brush were here monopolized for designs on wood or on copper. We have thus to account for the comparative unproductiveness as painters of Dürer and Holbein, and at the same time to explain the shallowness apparent in many of the later works of Cranach; but we attribute to the same cause also the tendency in Cranach to neglect effective colour and light and shade for strong contrasts of flat tint.

Constant attention to mere contour and to black and white appears to have affected his sight, and caused those curious transitions of pallid light into inky grey which often characterize his studies of flesh; whilst the mere outlining of form in black became a natural substitute for modelling and chiaroscuro. There are, no doubt, some few pictures by Cranach in which the flesh-tints display brightness and enamelled surface, but they are quite exceptional.

As a composer Cranach was not greatly gifted. His ideal of the human shape was low; but he showed some freshness in the delineation of incident, though he not unfrequently bordered on coarseness. His copper-plates and woodcuts are certainly the best outcome of his art; and the earlier they are in date the more conspicuous is their power. Striking evidence of this is the "St Christopher" of 1506, or the plate of "Elector Frederick praying before the Madonna" (1509).

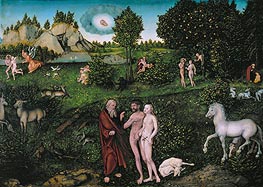

It is curious to watch the changes which mark the development of his instincts as an artist during the struggles of the Reformation. At first we find him painting Madonnas. His first woodcut (1505) represents the Virgin and three saints in prayer before a crucifix. Later on he composes the marriage of St Catherine, a series of martyrdoms, and scenes from the Passion. After 1517 he illustrates occasionally the old gospel themes, but he also gives expression to some of the thoughts of the Reformers. In a picture of 1518 at Leipzig, where a dying man offers "his soul to God, his body to earth, and his worldly goods to his relations," the soul rises to meet the Trinity in heaven, and salvation is clearly shown to depend on faith and not on good works. Again sin and grace become a familiar subject of pictorial delineation. Adam is observed sitting between John the Baptist and a prophet at the foot of a tree. To the left God produces the tables of the law, Adam and Eve partake of the forbidden fruit, the brazen serpent is reared aloft, and punishment supervenes in the shape of death and the realm of Satan. To the right, the Conception, Crucifixion and Resurrection symbolize redemption, and this is duly impressed on Adam by John the Baptist, who points to the sacrifice of the crucified Saviour. There are two examples of this composition in the galleries of Gotha and Prague, both of them dated 1529.

One of the latest pictures with which the name of Cranach is connected is the altarpiece which Cranach's son completed in 1555, and which is now (1911) in the Stadtkirche (city church) at Weimar. It represents Christ in two forms, to the left trampling on Death and Satan, to the right crucified, with blood flowing from the lance wound. John the Baptist points to the suffering Christ, whilst the blood-stream falls on the head of Cranach, and Luther reads from his book the words, "The blood of Christ cleanseth from all sin." Cranach sometimes composed gospel subjects with feeling and dignity. "The Woman taken in Adultery" at Munich is a favourable specimen of his skill, and various repetitions of Christ receiving little children show the kindliness of his disposition.

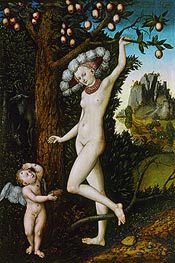

But he was not exclusively a religious painter. He was equally successful, and often comically naïve, in mythological scenes, as where Cupid, who has stolen a honeycomb, complains to Venus that he has been stung by a bee (Weimar, 1530; Berlin, 1534), or where Hercules sits at the spinning-wheel mocked by Omphale and her maids. Humour and pathos are combined at times with strong effect in pictures such as the "Jealousy" (Augsburg, 1527; Vienna, 1530), where women and children are huddled into telling groups as they watch the strife of men wildly fighting around them. Very realistic must have been a lost canvas of 1545, in which hares were catching and roasting sportsmen. In 1546, possibly under Italian influence, Cranach composed the "Fons Juventutis" ("Fountain of Youth") of the Berlin Gallery, executed by his son, a picture in which hags are seen entering a Renaissance fountain, and are received as they issue from it with all the charms of youth by knights and pages.

Cranach's chief occupation was that of portrait painting, and we are indebted to him chiefly for the preservation of the features of all the German Reformers and their princely adherents. But he sometimes condescended to depict such noted followers of the papacy as Albert of Brandenburg, archbishop elector of Mainz, Anthony Granvelle and the duke of Alva. A dozen likenesses of Frederick III and his brother John are found to bear the date of 1532. It is characteristic of Cranach's readiness, and a proof that he possessed ample material for mechanical reproduction, that he received payment at Wittenberg in 1533. for "sixty pairs of portraits of the elector and his brother" in one day. Amongst existing likenesses we should notice as the best that of Albert, elector of Mainz, in the Berlin museum, and that of John, elector of Saxony, at Dresden.

Cranach had three sons, all artists: John Lucas Cranach, who died at Bologna in 1536; Hans Cranach, whose life is obscure; and Lucas, born in 1515, who died in 1586.

Cranach's Attitudes Toward Women

This section attempts to extrapolate some of the regards Cranach may have held towards women by examining some of the letters he has written to Luther and some paintings that he had done which bore a religious theme.

Sources regarding Cranach's early life has indicated that he was in fact not a mysogynist, or a woman-hater. Far from it, he has been a friend and companion of girls and young maidens in his hometown of Cronach throughout his childhood and adolescence. As he had revealed in his diary, "I could never understand the attitudes held by common men towards that of the other gender. How could a gender with such grace, softness of voice, slender of curvature, fineness of appearance and exquisiteness of manners have been termed the seducer of Adam and be blamed for humanity's ultimate downfall from Eden, but alas, my mind is wandering on the dangerous fringe of hypocrisy and I must not allow this discourse to proceed any further.

In a later entry of Cranach's diary he has indicated the inspiration of some of his original artwork to have been stemmed from his observation of girls playing in the suburbs of his neighbourhoods on the "idle afternoons" when folks Cronach went for picnics and such, "I am all the more glad that the rules and customs of my homeland towards that of the fairer gender has been more laxed. Girls and younger maidens are oft seen playing and idling away one afternoon after another on the beautiful green pastures in the suburbs, along with the beautiful blue sky with the occasional cloud strewn about it like the graceful white gown of the young ladies,forms a picture that, in my mind, represents nothing less than a divine inspiration.I have recently completed several oil-canvas paintings of exclusive quality that depicted nothing but these beautiful afternoon suburb gatherings, in which you may occasionally find a single lone figure standing in the background, quietly appreciating God's handiwork and everything He hath provided for us, including the companion of this much superior gender, which through perhaps misfortunes of birth or accidents of fate has come to be known as the seducer of Men."

Later historical resources shows Cranach's marriage to his wife to be an exceedingly happy one. As Cranach notes again in his diary on the day of his marriage, "I have had the most fortune to have found myself a maiden whose virtue and beauty are unexceled by those of her peers. How kind God must have been on me, to have awarded me with such a graceful wife. Alas, I am so overjoyed that I have inadvertently treated wife as an object of inanimation, something to be awarded. Yet I must not think this way. I believe that my wife has been the most kind in entering this connubial contract with a man as petty as me, and if I were not to be able to provide to her in a manner that is not resonant with her material and emotional expectations, I shall be glad to let her go, to dissolve our communion at the risk of excommunication. But I know these things happenth not, for the marriage of her and I shall last to time indefinite." (Note that this diary entry was made before Martin Luther has launched the Protestant movement. So Cranach is by default a Catholic).

Cranach's diary entry at the time of the anniversary of his marriage confirmed his satisfactory married life with his wife and of his favorable opinion of women, "It has been a year now since we have wed. And I have often wondered how I could have made it through this year without the marriage. To me everyday for the past year has been an experience that I found delicious and savoring. To me the sun shone brighter and the birds chirpped merrier even though I know that to be just a effect of my heart, which has been made blisful by the presence of my beautiful wife. She is now 6 months pregnant with the protrusions being made more pronounced with each passing day. I sincerely hope it to be a daughter, despite assorted effusions to the contrary, I am personally convinced that I shall not be able to pamper a son as much as I do a daughter. But all in all, I find this matrimony to be of such an exceeding quality that I am beginning to doubt if my wife and I had been the very first couple to be placed in the Garden of Eden by God Himself, could Humanity have given into the temptation of the Devil and fell from the paradise in the first place? But this is heretical thinking, I must stop my idle personal musings here."

Later, Cranach's favorable opinions of the role of women and wives were re-inforced from the early teachings he has gained from Luther and the conversations that he had with Luther, many historic sources pointed to his thanking Luther at one point for the revelation that Protestantism (more specifically Lutheranism) has wrought to clarifying and codifying some of the budding opinions and hypothesis he has towards the virtues of women from the experience of his own married life. To which Luther replies with encouragement for Cranach to keep living the way he has lived before knowing Lutheranism and the fact that Cranach's matrimony has set an exemplery model to which all other Lutheran families at the time should follow. Thus encouraged, Cranach has written this as part of a missive of gratitude he has sent Luther circa 1514:

"...and exalted shall be He who hath the wisdom of creating this circle of matrimony in which man and woman come together to fill and subdue the Earthe with their procreative powers. And exhalted shall be He who hath made the companions of Men, even be they the supposed ones to have fallen to the Serpent's allure, the grace and softness with which they tend to their children and family shall have redeemed whatever sin they have committed to begin with ..."

However, as Lutherans become more established, their attitudes toward women gradually change from a positive one to a negative one, and Cranach was equally affected. Historic sources are scarce on the personal metamorphosis of Cranach from a stolid reverer and respecter of women to an individual with hints of mysogynism (Cranach was never a blantant discriminator of women due to the many years of reinforcements of positive images of women in his mind), but from the few that are shown it can be observed that a series of preachings given to Cranach through a local Lutheran minister acting directly under the order of Martin luther himself, designed to turn Cranach's favorable opinions of women around, has taken a dear toll on Cranach and his amity to women, to the point where his wife "barely recognises the man that was once her woman-loving husband". Cranach's mysogynism finally erupted in this letter that he sent to Luther circa 1523:

“It appears to me that the Catholics' treatise of their women is anything but permissive. Now that I have come to a profound revelation upon the materials taught by your [Luther's] new denomination, and I must say that it was of the utmost pleasure for me to have dawned upon the ultimate solution for the problem of pinpointing the women's place within our society. And much thanks to your [Luther's] preachings, I have discovered that the place is none other than the very sanctuary to the upholding of pure Christendom itself — the home. Yes! The place of the women belonged rightly to the home, they belonged not to the hypocritical austerity of celibacy which in my opinion is a blasphemous and gross distortion of the principles of God as manifested in the opening versus of Genesis, nor did they belong to the mundane and treacherous spheres of influence of men's world, for the multitude of intrigues and seductions will surely lead even the most pious woman astray and into a devious path of sin. Home is the place where a woman's heart, pure and good, doeth belong, it is a place where she will be provided in a manner consonant with her material needs and expectations, where her ravenous sexual urges with its voluptuous orgasmic delights will be competently entertained by her husband; and most importantly, to look after her offspring — from whence shall spring forth the future seeds of our nation and religion, and to the ultimate fulfillment of our covenant with Lord our Father, who art in heaven, about the multiplication and expansion of our kind to the very end of the corners of His Good Earthe.” A further communiqué from from Cranach to Luther, upon the completion of the Ten Commandments painting, revealed many thoughts hinting at his now evident misogynistic tinges. In the communiqué Cranach has professed to Luther that certain of his “new-found attitudes toward the fair sex”, supplemented and reinforced by later Lutheran teachings, have gone behind the production of the painting. From this communiqué we are seeing the beginnings of the theological sexism that is starting to cloud his earlier, rational judgment of women and their roles, which ultimately lead to his unfavorable portrayal of womankind in the aforementioned painting:

“I have sent you hither a recently completed painting on the Covenant of Man and God, and of the pleasant vices that are sinful in the eyes of our Creator. I have felt it to be a sublime masterpiece hitherto produced with my feeble talents, and all glories be to the Lord! I have decided upon oil painting as the best conduit of properly expressing the breadth and depth of the commandments, and as you can see the textures of the painting are rich and by utilizing certain techniques of oil paints I had been able to master a certain kind of optical effect, not unlike that of seeing through a looking glass, to bring out the divine and omnipresent characteristics of our Lord in the form of the crystalline rainbow shining upon the new world after the Flood. You might have also noticed, in the tabloids dealing with the first, the fifth, the sixth, the ninth and the tenth commandments, and in particular the tabloids dealing with the first, fifth, sixth and tenth, that I have taken the liberty of painting unclothed females and their anthropomorphic distortions as a hyperbolic device to further reinforce the image of the vice within the minds of my audience. There might perhaps be more dignifying ways of portraying the subjects of adultery and of men coveting their neighbour's wife without undue transgression of the fairer sex, for I certainly do not desire for it to be that way, I love my wife and believes her to be of the utmost grace and virtue, yet your preachings have opened my eyes to the world and the truth of the Scriptures, and I must say that I am having second opinions - perhaps my rendition of women in the painting has been unkind indeed, yet they are far from the state of falsehood.”

To which Martin Luther gleefully replied,

“It was a most exceptional rendition of Biblical account that I have gazed upon. And you should not be ashamed of your portrayal of women in these sinful states. After all, it was the unclothed Eve who has fallen prey to the cunning seductions of the Serpent and yielded to the Forbidden Fruit. No one will be made the wiser before the Original Sin, and we have our women to thank for that! If I were you, this painting would have looked ten-folds more rapacious and ravenous, why, I would have had the wife-coveting man and his lover totally unclothed, committing those unspeakable acts right in the back-drop of the dark-green trees and shrubs.”

He was born at Kronach in upper Franconia, and learned the art of drawing from his father. It has not been possible to trace his descent or the name of his parents. We are not informed as to the school in which he was taught, and it is a mere guess that he took lessons from the south German masters to whom Matthias Grunewald owed his education. But Grunewald practised at Bamberg and Aschaffenburg, and Bamberg is the capital of the diocese in which Cronach lies.

According to Gunderam, the tutor of Cranach's children, Cranach signalized his talents as a painter before the close of the 15th century. He then drew upon himself the attention of the elector of Saxony, who attached him to his person in 1504. The records of Wittenberg confirm Gunderam's statement to this extent that Cranach's name appears for the first time in the public accounts on the 24th of June 1504, when he drew 50 gulden for the salary of half a year, as pictor ducalis.

The only clue to Cranach's settlement previous to his Wittenberg appointment is afforded by the knowledge that he owned a house at Gotha, and that Barbara Brengbier, his wife, was the daughter of a burgher of that city.

The first evidence of his skill as an artist comes in a picture dated 1504. We find him active in several branches of his profession, sometimes a mere house-painter, more frequently producing portraits and altar-pieces, a designer on wood, an engraver of copper-plates, and draughtsman for the dies of the electoral mint. Early in the days of his official employment he startled his master's courtiers by the realism with which he painted still life, game and antlers on the walls of the country palaces at Coburg and Locha; his pictures of deer and wild boar were considered striking, and the duke fostered his passion for this form of art by taking him out to the hunting field, where he sketched "his grace" running the stag, or Duke John sticking a boar.

Before 1508 he had painted several altar-pieces for the Schlosskirche at Wittenberg in competition with Dürer, Hans Burgkmair and others; the duke and his brother John were portrayed in various attitudes and a number of the best woodcuts and copper-plates were published.

Great honour accrued to Cranach when he went in 1509 to the Netherlands, and took sittings from the Emperor Maximilian and the boy who afterwards became Charles V. Until 1508 Cranach signed his works with the initials of his name. In that year the elector gave him the winged snake as a motto, and this motto, or Kleinod, as it was called, superseded the initials on all his pictures after that date.

Somewhat later the duke conferred on him the monopoly of the sale of medicines at Wittenberg, and a printer's patent with exclusive privileges as to copyright in Bibles. The presses of Cranach were used by Martin Luther. His chemist's shop was open for centuries, and only perished by fire in 1871.

Relations of friendship united the painter with the Protestant Reformers at a very early period; yet it is difficult to fix the time of his first acquaintance with Luther. The oldest notice of Cranach in the Reformer's correspondence dates from 1520. In a letter written from Worms in 1521, Luther calls him his gossip, warmly alluding to his "Gevatterin," the artist's wife. His first engraved portrait by Cranach represents an Augustinian friar, and is dated 1520. Five years later the friar dropped the cowl, and Cranach was present as "one of the council" at the betrothal festival of Luther and Katarina von Bora.

The death at short intervals of the electors Frederick and John (1525 and 1532) brought no change in the prosperous situation of the painter; he remained a favourite with John Frederick I, under whose administration he twice (1531 and 1540) filled the office of burgomaster of Wittenberg. But 1547 witnessed a remarkable change in these relations. John Frederick was taken prisoner at the Battle of Mühlberg, and Wittenberg was subjected to the stress of siege. As Cranach wrote from his house at the corner of the marketplace to the grand-master Albert of Brandenburg at Königsberg to tell him of John Frederick's capture, he showed his attachment by saying, "I cannot conceal from your Grace that we have been robbed of our dear prince, who from his youth upwards has been a true prince to us, but God will help him out of prison, for the Kaiser is bold enough to revive the Papacy, which God will certainly not allow." During the siege Charles bethought him of Cranach, whom he remembered from his childhood and summoned him to his camp at Pistritz. Cranach came, reminded his majesty of his early sittings as a boy, and begged on his knees for kind treatment to the elector.

Three years afterwards, when all the dignitaries of the Empire met at Augsburg to receive commands from the emperor, and Titian came at Charles's bidding to paint Philip of Spain, John Frederick asked Cranach to visit the Swabian capital; and here for a few months he was numbered amongst the household of the captive elector, whom he afterwards accompanied home in 1552.

He died on the 16th of October 1553 at Weimar, where the house in which he lived still stands in the marketplace.

The oldest extant picture of Cranach, the "Rest of the Virgin during the Flight into Egypt," marked with the initials L.C., and the date of 1504, is by far the most graceful creation of his pencil. The scene is laid on the margin of a forest of pines, and discloses the habits of a painter familiar with the mountain scenery of Thuringia. There is more of gloom in landscapes of a later time.

Cranach's art in its prime was doubtless influenced by causes which but slightly affected the art of the Italians, but weighed with potent consequence on that of the Netherlands and Germany. The business of booksellers who sold woodcuts and engravings at fairs and markets in Germany naturally satisfied a craving which arose out of the paucity of wall paintings in churches and secular edifices. Drawing for woodcuts and engraving of copperplates became the occupation of artists of note, and the talents devoted in Italy to productions of the brush were here monopolized for designs on wood or on copper. We have thus to account for the comparative unproductiveness as painters of Dürer and Holbein, and at the same time to explain the shallowness apparent in many of the later works of Cranach; but we attribute to the same cause also the tendency in Cranach to neglect effective colour and light and shade for strong contrasts of flat tint.

Constant attention to mere contour and to black and white appears to have affected his sight, and caused those curious transitions of pallid light into inky grey which often characterize his studies of flesh; whilst the mere outlining of form in black became a natural substitute for modelling and chiaroscuro. There are, no doubt, some few pictures by Cranach in which the flesh-tints display brightness and enamelled surface, but they are quite exceptional.

As a composer Cranach was not greatly gifted. His ideal of the human shape was low; but he showed some freshness in the delineation of incident, though he not unfrequently bordered on coarseness. His copper-plates and woodcuts are certainly the best outcome of his art; and the earlier they are in date the more conspicuous is their power. Striking evidence of this is the "St Christopher" of 1506, or the plate of "Elector Frederick praying before the Madonna" (1509).

It is curious to watch the changes which mark the development of his instincts as an artist during the struggles of the Reformation. At first we find him painting Madonnas. His first woodcut (1505) represents the Virgin and three saints in prayer before a crucifix. Later on he composes the marriage of St Catherine, a series of martyrdoms, and scenes from the Passion. After 1517 he illustrates occasionally the old gospel themes, but he also gives expression to some of the thoughts of the Reformers. In a picture of 1518 at Leipzig, where a dying man offers "his soul to God, his body to earth, and his worldly goods to his relations," the soul rises to meet the Trinity in heaven, and salvation is clearly shown to depend on faith and not on good works. Again sin and grace become a familiar subject of pictorial delineation. Adam is observed sitting between John the Baptist and a prophet at the foot of a tree. To the left God produces the tables of the law, Adam and Eve partake of the forbidden fruit, the brazen serpent is reared aloft, and punishment supervenes in the shape of death and the realm of Satan. To the right, the Conception, Crucifixion and Resurrection symbolize redemption, and this is duly impressed on Adam by John the Baptist, who points to the sacrifice of the crucified Saviour. There are two examples of this composition in the galleries of Gotha and Prague, both of them dated 1529.

One of the latest pictures with which the name of Cranach is connected is the altarpiece which Cranach's son completed in 1555, and which is now (1911) in the Stadtkirche (city church) at Weimar. It represents Christ in two forms, to the left trampling on Death and Satan, to the right crucified, with blood flowing from the lance wound. John the Baptist points to the suffering Christ, whilst the blood-stream falls on the head of Cranach, and Luther reads from his book the words, "The blood of Christ cleanseth from all sin." Cranach sometimes composed gospel subjects with feeling and dignity. "The Woman taken in Adultery" at Munich is a favourable specimen of his skill, and various repetitions of Christ receiving little children show the kindliness of his disposition.

But he was not exclusively a religious painter. He was equally successful, and often comically naïve, in mythological scenes, as where Cupid, who has stolen a honeycomb, complains to Venus that he has been stung by a bee (Weimar, 1530; Berlin, 1534), or where Hercules sits at the spinning-wheel mocked by Omphale and her maids. Humour and pathos are combined at times with strong effect in pictures such as the "Jealousy" (Augsburg, 1527; Vienna, 1530), where women and children are huddled into telling groups as they watch the strife of men wildly fighting around them. Very realistic must have been a lost canvas of 1545, in which hares were catching and roasting sportsmen. In 1546, possibly under Italian influence, Cranach composed the "Fons Juventutis" ("Fountain of Youth") of the Berlin Gallery, executed by his son, a picture in which hags are seen entering a Renaissance fountain, and are received as they issue from it with all the charms of youth by knights and pages.

Cranach's chief occupation was that of portrait painting, and we are indebted to him chiefly for the preservation of the features of all the German Reformers and their princely adherents. But he sometimes condescended to depict such noted followers of the papacy as Albert of Brandenburg, archbishop elector of Mainz, Anthony Granvelle and the duke of Alva. A dozen likenesses of Frederick III and his brother John are found to bear the date of 1532. It is characteristic of Cranach's readiness, and a proof that he possessed ample material for mechanical reproduction, that he received payment at Wittenberg in 1533. for "sixty pairs of portraits of the elector and his brother" in one day. Amongst existing likenesses we should notice as the best that of Albert, elector of Mainz, in the Berlin museum, and that of John, elector of Saxony, at Dresden.

Cranach had three sons, all artists: John Lucas Cranach, who died at Bologna in 1536; Hans Cranach, whose life is obscure; and Lucas, born in 1515, who died in 1586.

Cranach's Attitudes Toward Women

This section attempts to extrapolate some of the regards Cranach may have held towards women by examining some of the letters he has written to Luther and some paintings that he had done which bore a religious theme.

Sources regarding Cranach's early life has indicated that he was in fact not a mysogynist, or a woman-hater. Far from it, he has been a friend and companion of girls and young maidens in his hometown of Cronach throughout his childhood and adolescence. As he had revealed in his diary, "I could never understand the attitudes held by common men towards that of the other gender. How could a gender with such grace, softness of voice, slender of curvature, fineness of appearance and exquisiteness of manners have been termed the seducer of Adam and be blamed for humanity's ultimate downfall from Eden, but alas, my mind is wandering on the dangerous fringe of hypocrisy and I must not allow this discourse to proceed any further.

In a later entry of Cranach's diary he has indicated the inspiration of some of his original artwork to have been stemmed from his observation of girls playing in the suburbs of his neighbourhoods on the "idle afternoons" when folks Cronach went for picnics and such, "I am all the more glad that the rules and customs of my homeland towards that of the fairer gender has been more laxed. Girls and younger maidens are oft seen playing and idling away one afternoon after another on the beautiful green pastures in the suburbs, along with the beautiful blue sky with the occasional cloud strewn about it like the graceful white gown of the young ladies,forms a picture that, in my mind, represents nothing less than a divine inspiration.I have recently completed several oil-canvas paintings of exclusive quality that depicted nothing but these beautiful afternoon suburb gatherings, in which you may occasionally find a single lone figure standing in the background, quietly appreciating God's handiwork and everything He hath provided for us, including the companion of this much superior gender, which through perhaps misfortunes of birth or accidents of fate has come to be known as the seducer of Men."

Later historical resources shows Cranach's marriage to his wife to be an exceedingly happy one. As Cranach notes again in his diary on the day of his marriage, "I have had the most fortune to have found myself a maiden whose virtue and beauty are unexceled by those of her peers. How kind God must have been on me, to have awarded me with such a graceful wife. Alas, I am so overjoyed that I have inadvertently treated wife as an object of inanimation, something to be awarded. Yet I must not think this way. I believe that my wife has been the most kind in entering this connubial contract with a man as petty as me, and if I were not to be able to provide to her in a manner that is not resonant with her material and emotional expectations, I shall be glad to let her go, to dissolve our communion at the risk of excommunication. But I know these things happenth not, for the marriage of her and I shall last to time indefinite." (Note that this diary entry was made before Martin Luther has launched the Protestant movement. So Cranach is by default a Catholic).

Cranach's diary entry at the time of the anniversary of his marriage confirmed his satisfactory married life with his wife and of his favorable opinion of women, "It has been a year now since we have wed. And I have often wondered how I could have made it through this year without the marriage. To me everyday for the past year has been an experience that I found delicious and savoring. To me the sun shone brighter and the birds chirpped merrier even though I know that to be just a effect of my heart, which has been made blisful by the presence of my beautiful wife. She is now 6 months pregnant with the protrusions being made more pronounced with each passing day. I sincerely hope it to be a daughter, despite assorted effusions to the contrary, I am personally convinced that I shall not be able to pamper a son as much as I do a daughter. But all in all, I find this matrimony to be of such an exceeding quality that I am beginning to doubt if my wife and I had been the very first couple to be placed in the Garden of Eden by God Himself, could Humanity have given into the temptation of the Devil and fell from the paradise in the first place? But this is heretical thinking, I must stop my idle personal musings here."

Later, Cranach's favorable opinions of the role of women and wives were re-inforced from the early teachings he has gained from Luther and the conversations that he had with Luther, many historic sources pointed to his thanking Luther at one point for the revelation that Protestantism (more specifically Lutheranism) has wrought to clarifying and codifying some of the budding opinions and hypothesis he has towards the virtues of women from the experience of his own married life. To which Luther replies with encouragement for Cranach to keep living the way he has lived before knowing Lutheranism and the fact that Cranach's matrimony has set an exemplery model to which all other Lutheran families at the time should follow. Thus encouraged, Cranach has written this as part of a missive of gratitude he has sent Luther circa 1514:

"...and exalted shall be He who hath the wisdom of creating this circle of matrimony in which man and woman come together to fill and subdue the Earthe with their procreative powers. And exhalted shall be He who hath made the companions of Men, even be they the supposed ones to have fallen to the Serpent's allure, the grace and softness with which they tend to their children and family shall have redeemed whatever sin they have committed to begin with ..."

However, as Lutherans become more established, their attitudes toward women gradually change from a positive one to a negative one, and Cranach was equally affected. Historic sources are scarce on the personal metamorphosis of Cranach from a stolid reverer and respecter of women to an individual with hints of mysogynism (Cranach was never a blantant discriminator of women due to the many years of reinforcements of positive images of women in his mind), but from the few that are shown it can be observed that a series of preachings given to Cranach through a local Lutheran minister acting directly under the order of Martin luther himself, designed to turn Cranach's favorable opinions of women around, has taken a dear toll on Cranach and his amity to women, to the point where his wife "barely recognises the man that was once her woman-loving husband". Cranach's mysogynism finally erupted in this letter that he sent to Luther circa 1523:

“It appears to me that the Catholics' treatise of their women is anything but permissive. Now that I have come to a profound revelation upon the materials taught by your [Luther's] new denomination, and I must say that it was of the utmost pleasure for me to have dawned upon the ultimate solution for the problem of pinpointing the women's place within our society. And much thanks to your [Luther's] preachings, I have discovered that the place is none other than the very sanctuary to the upholding of pure Christendom itself — the home. Yes! The place of the women belonged rightly to the home, they belonged not to the hypocritical austerity of celibacy which in my opinion is a blasphemous and gross distortion of the principles of God as manifested in the opening versus of Genesis, nor did they belong to the mundane and treacherous spheres of influence of men's world, for the multitude of intrigues and seductions will surely lead even the most pious woman astray and into a devious path of sin. Home is the place where a woman's heart, pure and good, doeth belong, it is a place where she will be provided in a manner consonant with her material needs and expectations, where her ravenous sexual urges with its voluptuous orgasmic delights will be competently entertained by her husband; and most importantly, to look after her offspring — from whence shall spring forth the future seeds of our nation and religion, and to the ultimate fulfillment of our covenant with Lord our Father, who art in heaven, about the multiplication and expansion of our kind to the very end of the corners of His Good Earthe.” A further communiqué from from Cranach to Luther, upon the completion of the Ten Commandments painting, revealed many thoughts hinting at his now evident misogynistic tinges. In the communiqué Cranach has professed to Luther that certain of his “new-found attitudes toward the fair sex”, supplemented and reinforced by later Lutheran teachings, have gone behind the production of the painting. From this communiqué we are seeing the beginnings of the theological sexism that is starting to cloud his earlier, rational judgment of women and their roles, which ultimately lead to his unfavorable portrayal of womankind in the aforementioned painting:

“I have sent you hither a recently completed painting on the Covenant of Man and God, and of the pleasant vices that are sinful in the eyes of our Creator. I have felt it to be a sublime masterpiece hitherto produced with my feeble talents, and all glories be to the Lord! I have decided upon oil painting as the best conduit of properly expressing the breadth and depth of the commandments, and as you can see the textures of the painting are rich and by utilizing certain techniques of oil paints I had been able to master a certain kind of optical effect, not unlike that of seeing through a looking glass, to bring out the divine and omnipresent characteristics of our Lord in the form of the crystalline rainbow shining upon the new world after the Flood. You might have also noticed, in the tabloids dealing with the first, the fifth, the sixth, the ninth and the tenth commandments, and in particular the tabloids dealing with the first, fifth, sixth and tenth, that I have taken the liberty of painting unclothed females and their anthropomorphic distortions as a hyperbolic device to further reinforce the image of the vice within the minds of my audience. There might perhaps be more dignifying ways of portraying the subjects of adultery and of men coveting their neighbour's wife without undue transgression of the fairer sex, for I certainly do not desire for it to be that way, I love my wife and believes her to be of the utmost grace and virtue, yet your preachings have opened my eyes to the world and the truth of the Scriptures, and I must say that I am having second opinions - perhaps my rendition of women in the painting has been unkind indeed, yet they are far from the state of falsehood.”

To which Martin Luther gleefully replied,

“It was a most exceptional rendition of Biblical account that I have gazed upon. And you should not be ashamed of your portrayal of women in these sinful states. After all, it was the unclothed Eve who has fallen prey to the cunning seductions of the Serpent and yielded to the Forbidden Fruit. No one will be made the wiser before the Original Sin, and we have our women to thank for that! If I were you, this painting would have looked ten-folds more rapacious and ravenous, why, I would have had the wife-coveting man and his lover totally unclothed, committing those unspeakable acts right in the back-drop of the dark-green trees and shrubs.”

262 Lucas Cranach Paintings

Portrait of Dr. Johannes Cuspinian c.1502/03

Oil Painting

$2201

$2201

Canvas Print

$63.99

$63.99

SKU: CLE-3139

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 59 x 45 cm

Oskar Reinhart Museum, Winterthur, Switzerland

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 59 x 45 cm

Oskar Reinhart Museum, Winterthur, Switzerland

Anna Putsch, First Wife of Dr. Johannes Cuspinian c.1502/03

Oil Painting

$2201

$2201

Canvas Print

$64.46

$64.46

SKU: CLE-3140

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 59 x 45 cm

Oskar Reinhart Museum, Winterthur, Switzerland

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 59 x 45 cm

Oskar Reinhart Museum, Winterthur, Switzerland

Venus and Cupid 1509

Oil Painting

$2320

$2320

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-3141

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 213 x 102 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 213 x 102 cm

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

Portrait of Elector Frederick the Wise c.1532

Oil Painting

$1919

$1919

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-4211

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 80 x 49 cm

Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna, Austria

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 80 x 49 cm

Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna, Austria

Lucretia 1532

Oil Painting

$1639

$1639

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-4212

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 37.5 x 24.5 cm

Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna, Austria

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 37.5 x 24.5 cm

Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna, Austria

Venus and Cupid Stealing Honey 1531

Oil Painting

$1795

$1795

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-8482

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 169 x 67 cm

Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 169 x 67 cm

Galleria Borghese, Rome, Italy

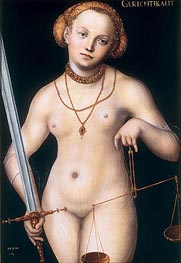

Allegory of Justice 1537

Oil Painting

$1853

$1853

Canvas Print

$58.71

$58.71

SKU: CLE-11672

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 72 x 49.6 cm

Private Collection

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 72 x 49.6 cm

Private Collection

Lot and His Daughters n.d.

Oil Painting

$2940

$2940

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-13979

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: unknown

Museum der Bildenden Kunste, Leipzig, Germany

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: unknown

Museum der Bildenden Kunste, Leipzig, Germany

Eve 1537

Oil Painting

$1871

$1871

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-13980

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 137 x 54 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 137 x 54 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Adam 1537

Oil Painting

$1813

$1813

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-13981

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 137 x 54 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 137 x 54 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

The Fall a.1537

Oil Painting

$2717

$2717

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-13982

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 53.3 x 37.1 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 53.3 x 37.1 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Judith with the Head of Holofernes c.1530

Oil Painting

$2734

$2734

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-13983

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 87 x 56 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 87 x 56 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Portrait of Martin Luther 1529

Oil Painting

$1548

$1548

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-13984

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 36.5 x 23 cm

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 36.5 x 23 cm

Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, Italy

Saint Dorothy Receiving Roses from a Young Boy ... 1506

Oil Painting

$3798

$3798

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-13985

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 139 x 70 cm

Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 139 x 70 cm

Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

Saints Barbara, Ursula and Margaret (St. ... 1506

Oil Painting

$3874

$3874

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-13986

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 139 x 70 cm

Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 139 x 70 cm

Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

The Martyrdom of Saint Catherine (St. Catherine ... 1506

Oil Painting

$14516

$14516

Canvas Print

$95.83

$95.83

SKU: CLE-13987

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 139 x 156 cm

Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 139 x 156 cm

Gemaldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden, Germany

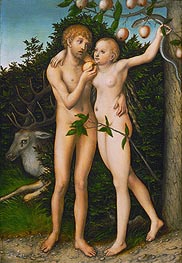

Adam and Eve n.d.

Oil Painting

$2340

$2340

Canvas Print

$73.31

$73.31

SKU: CLE-13988

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 59 x 44 cm

National Museum, Warsaw, Poland

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 59 x 44 cm

National Museum, Warsaw, Poland

Cupid Complaining to Venus c.1525

Oil Painting

$3105

$3105

Canvas Print

$56.69

$56.69

SKU: CLE-13989

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 81.3 x 54.6 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 81.3 x 54.6 cm

National Gallery, London, UK

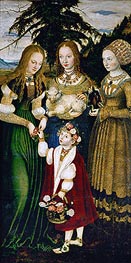

The Princesses Sibylla, Emilia and Sidonia of Saxony c.1535

Oil Painting

$3521

$3521

Canvas Print

$57.93

$57.93

SKU: CLE-13990

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 62 x 89 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 62 x 89 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Paradise (Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden) 1530

Oil Painting

$3545

$3545

Canvas Print

$60.57

$60.57

SKU: CLE-13991

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 81 x 114 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 81 x 114 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Judith with the Head of Holofernes and a Servant c.1537

Oil Painting

$2750

$2750

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-13992

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 75.2 x 51 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 75.2 x 51 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

Venus in a Landscape 1529

Oil Painting

$1588

$1588

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-13993

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 38 x 25 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 38 x 25 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

The Silver Age (The Effects of Jealousy) 1535

Oil Painting

$3012

$3012

Canvas Print

$56.54

$56.54

SKU: CLE-13994

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 77.5 x 52.5 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: 77.5 x 52.5 cm

Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Reclining Water Nymph n.d.

Oil Painting

$2175

$2175

Canvas Print

$56.36

$56.36

SKU: CLE-13995

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: unknown

Museum der Bildenden Kunste, Leipzig, Germany

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Original Size: unknown

Museum der Bildenden Kunste, Leipzig, Germany